Could you introduce yourself and tell us about your background?

I am an assistant engineer, the head of the or SBEA (Animal Welfare Body) and a member of an Comités d'éthique en expérimentation animale or CEEA (animal experimentation ethics committees). I co-lead the 'Ethics and Welfare' group, and I am also a member of the 'Transgenesis' group within the national research infrastructure Celphedia.

I have over 24 years' experience in animal experimentation. I began my career as a junior employee at the Faculty of Medicine in Rouen. After passing the CNRS external competitive examinations, I worked as a breeding technician at the Animal Model Typing and Archiving Support and Research Unit (UAR TAAM) in Orléans and at the Rousset primatology station.

Since 2017, I have worked as a technician and subsequently as an assistant engineer at the hTAG Support and Research Unit in Grenoble.

I have long been committed to the welfare of various animal species, I would like to thank all the organisations and animal facility managers who have enabled me to discover the richness and diversity of this field, and to cultivate my passion for it.

Please tell us about the 3Rs and the culture of care in your laboratory on a daily basis?

Since becoming an SBEA manager in 2022, I have initiated and supported numerous changes to practices and attitudes, with the aim of promoting a more respectful approach to animal welfare.

These changes include:

-

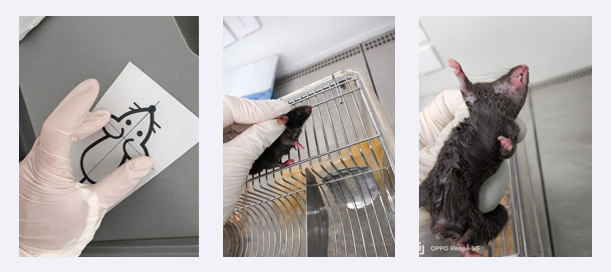

replacing the use of forceps to restrain animals with more humane methods, such as cupping, using tunnels or restraining them by the scruff of their neck when necessary;

-

abandoning phalangectomy in favour of tattooing the phalanges for animal identification;

-

implementing training courses, including those outside my own establishment, to disseminate these good practices.I have also introduced new methods and enrichment activities, including three-finger restraint, creating "play areas" for rats and developing and structuring tickling practices.

Studies have shown that two-finger restraint creates a longitudinal skin fold, stretching the skin around the throat and trachea. This causes stress to the animal and severe bradyarrhythmias that persist for four minutes after release. In line with Norecopa's recommendations, we adopted three-finger restraint and introduced this technique across the entire animal facility.

During playtime and tickling sessions, the rats are placed in a transfer isolator containing various items for them to discover and explore, such as tubes, houses, grids and crimped wire, as well as a cage filled with water. After a few minutes, the animal technician begins to interact with the rats using their hands and proceeds to 'tickle' them. This technique comprises three main elements: 'dorsal contact' on the rat's neck; a 'pinch' on the rat's belly; and 'tickling'. In the Panksepp method, 15 seconds of hand contact is alternated with 15 seconds of no contact, for a total of two minutes.

My commitment is unwavering. I am always thinking of new ways to improve the application of the 3Rs, enhance animal welfare, and develop enrichment practices within teams.

How can these advances be shared with the scientific community?

I recently gave a presentation on best practices in animal experimentation to medical students, together with our organisation's veterinary consultant, Mr Bertrand Favier.

In 2024, I provided tattooing training to several teams at various animal facilities in Grenoble, and delivered a presentation on rodent handling methods as part of the Designer-level training course.

Although I am rather reserved by nature, I am nevertheless committed to changing attitudes. With this in mind, I joined the Celphedia working group, where I met other professionals who were eager to discuss innovative techniques.

In 2025, I presented the 'Tickling' method at the AFSTAL conference. Eager to maintain this momentum, I am fully committed to my ethics and animal welfare working group. We responded to a call for tenders and obtained Celphedia's support for the 'Tickling' project. I am currently awaiting the results of the FC3R Refinement call for tenders, for which I submitted a project.

I have also been asked to write an article for the STAL scientific journal in 2026. I plan to submit a short paper to AFSTAL 2026, and I have also been invited to present my work at the Grenoble Animal Facilities Group conference.

My main goal is to disseminate these techniques on a national scale and make a lasting impression on the people I have met while working in the field of animal welfare. The positive feedback I receive is a real source of motivation and satisfaction.

What does the 3R 'Culture of Care' Award mean to you?

Winning this award would strongly recognise my daily commitment to animal welfare and the culture of care. Despite the constant involvement it requires, this work is still too often invisible and insufficiently valued.

For several years, I have been thinking constantly about how to make concrete improvements at the grassroots level to change practices and attitudes. My drive for continuous improvement is deeply ingrained.

As a former high-level competitor, I developed discipline and mental strength, and these qualities have always accompanied me, driving me to strive for excellence and achieve my goals. This is particularly true with regard to the evolution of professional practices and the dissemination of a demanding yet respectful culture of care.

I am deeply passionate about my work and animal behaviour, particularly that of non-human primates. I would like to thank the managers and colleagues who have supported me throughout my career, during which time I have remained driven by my passion and desire to progress and share my knowledge.